See the World’s Largest Collection of Fluorescent Rocks

|

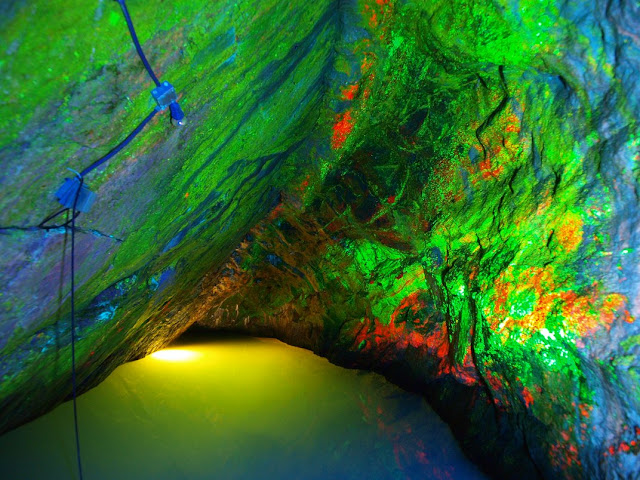

| Inside the Rainbow Tunnel. Credit: Jeff Glover |

And get glowing in this mine’s Rainbow Tunnel

In a New Jersey mine spanning 2,670 vertical feet—more than twice as deep as the Empire State Building is tall—visitors might notice a little glow. Well, a lot of glow, actually.

The Sterling Hill Mining Museum is known to have the world’s largest publicly displayed collection of fluorescent rocks—ones that beam bright neon colors under certain types of light. The museum is an old zinc mine—one of the oldest in the country, having opened in 1739 and in operation until 1986, during which time it was an important site for hauling out zinc, as well as iron and manganese. The abandoned mine was purchased in 1989 and converted to a museum in 1990, and now welcomes about 40,000 people every year. The museum itself includes both outdoor and indoor mining exhibits, rock and fossil discovery centers, an observatory, an underground mine tour, and the Thomas S. Warren Museum of Fluorescence devoted to the glowing minerals.

The fluorescence museum occupies the mine’s old mill, a structure dating to 1916. There’s about 1,800 square feet of space, with more than two dozen exhibits—some of which you can touch and experience on your own. Even the entrance is impressive; more than 100 huge fluorescent mineral specimens cover an entire wall that’s lit up by different types of ultraviolet light, displaying the glowing capabilities of each mineral type. For kids, there’s a “cave,” complete with a fluorescent volcano, a castle, and some glowing wildlife. And there’s an exhibit comprised solely of fluorescent rocks and minerals from Greenland. All told, more than 700 objects are on display in the museum.

About 15 percent of minerals fluoresce under blacklight, and they generally don’t glow in the daytime. Essentially, ultraviolet light shining on these minerals is absorbed into the rock, where it reacts with chemicals in the material, and excites the electrons in the mineral, thus emitting that energy as an outwardly glow. Different types of ultraviolet light—longwave and shortwave—can produce different colors from the same rock, and based on other materials inside the mineral or cutting through a rock (called activators), it may glow multiple colors.

“A mineral might pick up different activators depending on where it forms, so a specimen from Mexico might fluoresce a different color than one from Arizona, even though it’s the same mineral,” Jill Pasteris, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University, told the college’s newspaper. “On the other hand, some minerals are just good fluorescers. Calcite, for example, can glow in just about all the fluorescent colors. But, oddly enough, having too much of an activator can prevent fluorescence as well. So an overdose of a generalized activator like manganese can keep a good fluorescer like calcite from lighting up.”

Among the most impressive parts of the mine tour at Sterling Hill is the walk through the Rainbow Tunnel, which ends in an entire fluoresced room called the Rainbow Room. Much of the route is illuminated by ultraviolet light, causing a burst of glowing, neon reds and greens from the exposed zinc ore in the walls. The green color signifies a different type of zinc ore called willemite. The mineral’s color can vary wildly in the daylight—everything from the typical chunks of reddish-brown to crystallized and gem-like blues and greens—but it fluoresces bright neon green. When the mine was active, the ore covered the walls throughout, so anyone shining ultraviolet light would have had a similar experience to what occurs in the tunnel today.

|

| Inside the Rainbow Tunnel. Credit: Jeff Glover |

|

| Inside the Rainbow Tunnel. Credit: Jeff Glover |

|

| Inside the Rainbow Tunnel. Credit: Jeff Glover |

The above post is reprinted from Smithsonian.com. the original article was written by Jennifer Billock